The art market's preference for young artists has been a recent topic on a couple of other art blogs. Edward Winkleman has an open thread, Hatin' how they love them Youngins and Lisa Hunter has picked the theme up on The Intrepid Art Collector blog with Deja vu all over again.

I started to respond to Lisa's remark "... doesn't anyone besides me remember the 80s? It was the same when we were 20. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Jeff Koons -- they were all in their 20s when they got famous…" but my thoughts rambled on to long for a comment.

(Lisa) You're right with the personalities, this was true also in the 60's Johns, Rauschenberg, Stella, Poons were all young as well. It might be generational. Typically artists near the age of 30 are the ones making the waves, setting the new stylistic trends. There are some big differences in how the art educational system and the business of art itself has changed over the last 40 years.

In the 1960's, the idea of being an artist as a "career" didn't really exist. By "career" I mean something akin to being a engineer at IBM, or an accountant, where if you got a college degree, you would get a job and a rung somewhere on the corporate ladder. By contrast, art schools, including the few universities which even had an MFA program, primarily taught art fundamentals and art history, the techniques of the trade, any mention of survival after graduation was anecdotal.

In the 1980's, partly as a result of the success of Minimalism, POP Art and Conceptual art, along with the appearance of new magazines like ArtForum, young artists came out of art schools with some idea that being an artist was a career. I think that in the mid 70's some of the art schools at least made an informal attempt to educate their students on what they should do to enter the system. That if you did the "right things" and made decent work, you could get a job (gallery) or even dream of being on the cover of ArtForum.

Fast forward, at the present, in addition to art fundamentals, the art schools also cover, either directly or indirectly, topics more directly related to establishing an art career including "art theory". The MFA has become a variant of the MBA and the "best students" from the "best schools" will get the "best jobs" This appears to be currently true.

The second major difference concerns the art business itself.

In the post WWII period, starting in the 1950's, with the shift in focus from Paris to the US (New York), the art business has grown substantially. Each of the three periods I outlined above, was marked by an increasing amount of capital purchasing "new art" As this trend developed, it became apparent that there could be a substantial return on investment if a collector purchased the early work of an artist who later became prominent. (hot)

This may seem like an obvious conclusion but it is not quite the case. In Los Angeles in the 1960's, the Irving Blum Gallery gave Andy Warhol his first exhibition of the Soup Cans. I think a few were slated to be sold (at around a $100 each but I could be wrong about that) when Mr. Blum decided that the set of 30 (??) paintings should be kept together and bought them himself. In essence he became a collector rather than a dealer. A collector, not a speculator, for he held the paintings for at least 30 years (I vaguely recall they may have finally been donated to a museum, I'm not sure)

The 1980's saw the birth of the art speculator, as a class of clientele, and the use of the "auction" as a method of establishing or raising prices. Prices of "emerging artists" were "augmented" through the auction market. Artworks were bought from an artist or dealer, sometimes by 2-3 people who each owned a "share", put up for auction and bought back by another collector who wanted the "unavailable" work, obviously pricing took a big jump and the "art speculator" was born.

A rising price has an interesting psychological affect, it creates demand. In the late 1970's, Phillip Guston's dealer could not sell his late new paintings (the ones people today love) at a price of $10,000. Even though they were great paintings, it seems that there was not much interest, collectors wanted paintings in his "established style". On day, his dealer told him over the phone, "Phillip, I've just doubled the value of your inventory" and doubled the asking (retail) prices, the rest is history.

At the present, none of the above observations have been lost on either side. Young artists are taught/encouraged to develop "a body of work" and the means of marketing it as a product. (there is a wide ranging definition for the word "product") As long as the art market stays firm, the speculators are prepared to take advantage of the situation by snapping up the work presumably with the intent of selling it later.

The fact that artists have become careerist, in the corporate sense, helps reduce the purchase risk. I suspect that, in a hot market for an artist, access to the work becomes somewhat constrained and is afforded to the "best clients". Again this is not unusual, with the exception that the speculators have a decided interest in seeing prices appreciate and may help things along where possible.

I suppose one should view this as a win-win situation for all concerned, the gallery, the collector, the speculator and of course the artist. On the consumer end, I believe this is true a good art market and appreciating prices is beneficial. For the artist, I suspect it may be a double edge sword. On the one hand, for artists with a degree of emotional maturity, the financial success may allow them more time to develop their artwork, more time to experiment and confidence, which should not to be underestimated as a developmental force. On the other hand, the pressures of financial success may weigh on the young artist by creating constraints, stylistic and otherwise, for which they are not prepared.

Whatever, it is what it is. As long as the art market stays firm, good or bad, I suspect the situation will continue. Further, an historical precedent has been set, and even if the art market crashed, the situation will be the same when it arises from the ashes again.

Today is some young persons "good old days"

Saturday, June 24, 2006

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

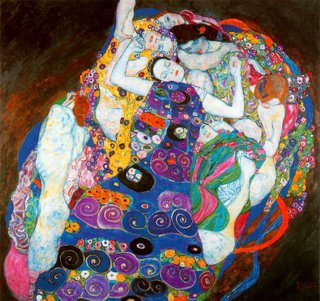

More Gustav Klimt

After the making the previous post, I thought it might be interesting to take a further look at some of Klimt's work. The stylistic focus on line and patterning made me think of the Dubuffet paintings I saw recently at Pace Gallery. Also at the time these paintings were made, the Japanese print had become to the forefront. In my view, Klimt took something from this but made it more uniquely personal.

It also occurred to me that at the moment the zeitgeist favors paintings which are have complicated linear detail. While Klimt may be dismissed by some as "decorative" there seems to be something here worth investigating, I'll append more to this commentary after I think about it awhile.

It also occurred to me that at the moment the zeitgeist favors paintings which are have complicated linear detail. While Klimt may be dismissed by some as "decorative" there seems to be something here worth investigating, I'll append more to this commentary after I think about it awhile.

Gustave Klimt, Austria. (1862-1918)

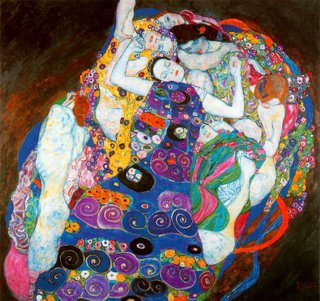

1913, The Maiden (Virgin)

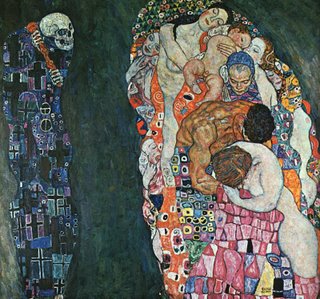

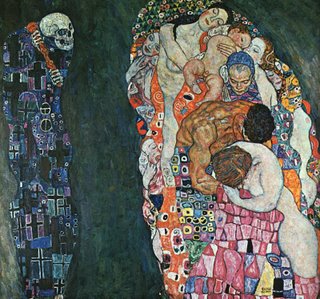

Gustave Klimt, 1916,

Death and Life

In 1918 the "Spanish Flu" Influenza (1916-1918) becomes pandemic; over twenty-five million people die in the following six months (almost twice the number that died during World War I which was also raging at the time).

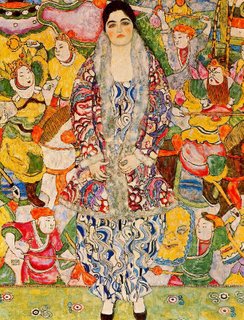

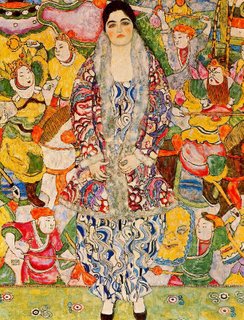

Gustave Klimt, 1916,

Portrait of Friedericke Maria Beer

Gustave Klimt, 1916,

Garden Path with Chickens

Monday, June 19, 2006

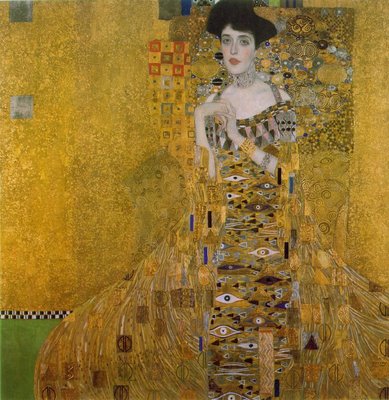

Gustav Klimt sets record

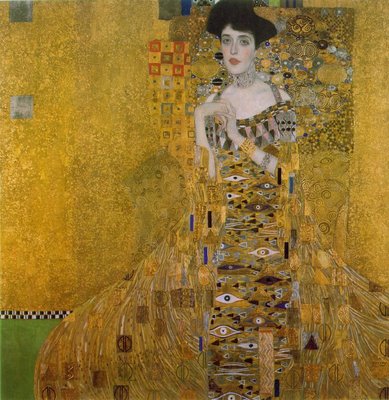

"A dazzling gold-flecked 1907 portrait by Gustav Klimt has been purchased for the Neue Galerie in Manhattan by the cosmetics magnate Ronald S. Lauder for $135 million, the highest sum ever paid for a painting."

From the New York Times, Monday June 19, 2006)

Some historical background from the Los Angeles County Museum including pictures of the other four paintings mentioned in the NY Times article

From the New York Times, Monday June 19, 2006)

Gustav Klimt, "Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I" 1907,

Oil and gold on canvas 138 x 138 cm

Photo NY Times.

A different photograph of the same painting.

Photo art Archive.

Some historical background from the Los Angeles County Museum including pictures of the other four paintings mentioned in the NY Times article

Sunday, June 11, 2006

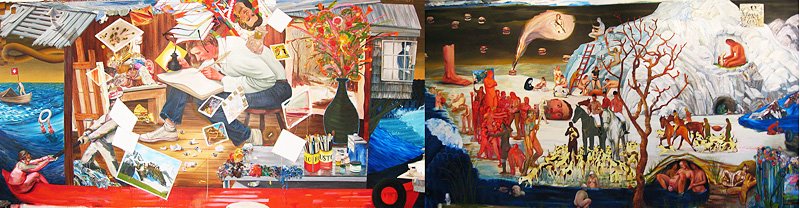

Nicole Eisenman at Leo Konig

Nicole Eisenman's new painting, Progress: Real and Imagined is heroic, both operatic in scope and monumental in scale. The best painting of the 2006 season.

Closes: June 17th, 2006

I went to Nicole Eisenman's opening, outside of reproductions, it was the first time had actually seen any of her work. While I was impressed with the scale of her new painting, it was hard to see because of the crowd. When I left, I wasn't sure what I thought of it. The memory of Progress: Real and Imagined stayed with me, like a gnawing in ones stomach, and I went back to see it again three more times. After my second viewing I knew I wanted to write something about it, but it took awhile to compose my thoughts.

Progress: Real and Imagined is a monumental painting, overall it is 8 feet high by 30 feet wide. It was painted on two canvases, the left is 16 feet wide and the right is shorter at just 14 feet, with a slight separation between the two. Generally, contemporary paintings of this scale, can be organized either as a permutative repetition of a conceptual idea which then becomes a pattern, as a visual field like Monet's Water Lilies, as the result of a physical process like pouring 20 gallons of paint on a canvas, or just by scaling the concept up. Eisenman's approach is none of the above.

I viewed her painting again Saturday with a friend, another painter who admittedly had some difficulty with the work, but who also conceded that it was masterfully organized. I became curious whether this was just brilliantly intuitive, like Jean Michel Basquiat, or the result of an application of a more arcane geometry. What I found was that it is classically organized, referring back to the methods of the Renaissance. Eisenman uses a sequences of divisions, diagonals and the golden section, somewhat like the diagram I posted earlier on Fra Angelico as a scaffold for her paintings flood of images. A painting, with as complex aggregation of images like "Progress: Real and Imagined", requires a degree of organization which creates a visual resonance among its parts or it will fragment into chaos.

Initially I thought there might be some similarity of approach between Eisenman's painting and the paintings of Basquiat and Dubuffet. I mused over the speculation that all three used a "stream of consciousness" approach in creating their works. With Eisenman, this may be the case but discovering the underlying geometric structure of her painting, along with her more deliberate approach to realizing her imagery, leads me to believe it is more of an extension of the approach of these two artists than a direct similarity.

Another factor engendered by the large scale is time. Without knowing for a fact, I suspect "Progress: Real and Imagined" must have taken close to a year to realize. Since this painting is not a repetition of sequential permutations but rather an aggregation of images, the time spent in its execution probably had an affect on the development of the paintings imagery.

A little digression, that afternoon, I also saw Jenney Holtzer's exhibition "Archive" at Cheim & Read. The Saturday crowd of viewers were dutifully arrayed, necks craned, reading the text of the paintings. This struck me as somewhat odd, but there was text to be read and they did.

I also observed how the viewers looked at Eisenman's painting. Since there is nothing to be read sequentially, the dance was different, eyes darted as they walked along, back and forth, in front of the painting. I believe painting is a language, what do viewers see when they cannot read something? The viewer is compelled to reconcile an image, or sequences of images, to imply or decode meaning. A painting is a "random access" visual experience, imagery can be perceived non-sequentially without the structure of a grammar and is processed differently. The eye-brain decodes a gestalt, three dots and a line might be a face, and then proceeds with a cascade on finer distinctions which may eventually be classified linguistically. This also evokes the viewers experience and memory about images, about painting, other images and other experiences. It is a more fluid and complex process than just decoding a word.

Eisenman's imagery can frequently be raw, grating, horrific, disturbing, sexual and not always ingratiating for the viewer. When confronted with the complexity of a painting like "Progress: Real and Imagined", the viewer may suffer overload or the anxiety of interpretation. It is this anxiety which creates the emotional tension, is there progress? Is it real or imagined?

Reading from right to left, we scan from the caveman to the artist in the studio, is this progress? Or not, since reading in the more familiar mode from left to right, goes the other way encountering the more brutal signs of a throwback, a decapitated head and a severed foot. During the paintings gestation period, the news was flooded with stories of a continuing war, of atrocities, natural disasters and corruption. Paintings have a mind of their own, once started they take the artist in a direction, and either subconsciously or by intent, life events become part of the process. This is in part what I was referring to above about how the time affects the imagery of the painting. Is that just a vase with flowers in the center of the painting, or is it some dreadful fireworks from a bomb which just killed a family? This kind of recursive interpretation, could go on for hours, the painting is an sheaf of images capable of constantly unfolding to engage the viewer.

One final observation. "Progress: Real and Imagined" is also complex in its stylistic resolution. Eisenman's painting, firmly structured, runs the stylistic gauntlet from the sweeping to the intimate. The little "throwaway" pictures in the studio are fully resolved in their own right. Her painterliness traverses a range from cursory to crusty congealed passages. It is obvious these variations are by choice, not constraint, for her observational powers are keen as seen in the rendering of the jeans of the artist at work. By expanding her range of execution, she in effect, detaches it from "style" and allows it to function as a tool of expression.

Nicole Eisenman's painting, Progress: Real and Imagined is an ambitious statement, an expansion of her vision. It is the type of painting I was hoping to see at the start of a new century, it is Future Modern.

PS:

I wanted to extend a special thanks to James Wagner and Barry Hoggard for introducing me to the artist.

Closes: June 17th, 2006

I went to Nicole Eisenman's opening, outside of reproductions, it was the first time had actually seen any of her work. While I was impressed with the scale of her new painting, it was hard to see because of the crowd. When I left, I wasn't sure what I thought of it. The memory of Progress: Real and Imagined stayed with me, like a gnawing in ones stomach, and I went back to see it again three more times. After my second viewing I knew I wanted to write something about it, but it took awhile to compose my thoughts.

Nicole Eisenman,“Progress: Real and Imagined”

Oil on canvas, 96 inches x 360 inches

Progress: Real and Imagined is a monumental painting, overall it is 8 feet high by 30 feet wide. It was painted on two canvases, the left is 16 feet wide and the right is shorter at just 14 feet, with a slight separation between the two. Generally, contemporary paintings of this scale, can be organized either as a permutative repetition of a conceptual idea which then becomes a pattern, as a visual field like Monet's Water Lilies, as the result of a physical process like pouring 20 gallons of paint on a canvas, or just by scaling the concept up. Eisenman's approach is none of the above.

I viewed her painting again Saturday with a friend, another painter who admittedly had some difficulty with the work, but who also conceded that it was masterfully organized. I became curious whether this was just brilliantly intuitive, like Jean Michel Basquiat, or the result of an application of a more arcane geometry. What I found was that it is classically organized, referring back to the methods of the Renaissance. Eisenman uses a sequences of divisions, diagonals and the golden section, somewhat like the diagram I posted earlier on Fra Angelico as a scaffold for her paintings flood of images. A painting, with as complex aggregation of images like "Progress: Real and Imagined", requires a degree of organization which creates a visual resonance among its parts or it will fragment into chaos.

Initially I thought there might be some similarity of approach between Eisenman's painting and the paintings of Basquiat and Dubuffet. I mused over the speculation that all three used a "stream of consciousness" approach in creating their works. With Eisenman, this may be the case but discovering the underlying geometric structure of her painting, along with her more deliberate approach to realizing her imagery, leads me to believe it is more of an extension of the approach of these two artists than a direct similarity.

Another factor engendered by the large scale is time. Without knowing for a fact, I suspect "Progress: Real and Imagined" must have taken close to a year to realize. Since this painting is not a repetition of sequential permutations but rather an aggregation of images, the time spent in its execution probably had an affect on the development of the paintings imagery.

A little digression, that afternoon, I also saw Jenney Holtzer's exhibition "Archive" at Cheim & Read. The Saturday crowd of viewers were dutifully arrayed, necks craned, reading the text of the paintings. This struck me as somewhat odd, but there was text to be read and they did.

I also observed how the viewers looked at Eisenman's painting. Since there is nothing to be read sequentially, the dance was different, eyes darted as they walked along, back and forth, in front of the painting. I believe painting is a language, what do viewers see when they cannot read something? The viewer is compelled to reconcile an image, or sequences of images, to imply or decode meaning. A painting is a "random access" visual experience, imagery can be perceived non-sequentially without the structure of a grammar and is processed differently. The eye-brain decodes a gestalt, three dots and a line might be a face, and then proceeds with a cascade on finer distinctions which may eventually be classified linguistically. This also evokes the viewers experience and memory about images, about painting, other images and other experiences. It is a more fluid and complex process than just decoding a word.

Eisenman's imagery can frequently be raw, grating, horrific, disturbing, sexual and not always ingratiating for the viewer. When confronted with the complexity of a painting like "Progress: Real and Imagined", the viewer may suffer overload or the anxiety of interpretation. It is this anxiety which creates the emotional tension, is there progress? Is it real or imagined?

Reading from right to left, we scan from the caveman to the artist in the studio, is this progress? Or not, since reading in the more familiar mode from left to right, goes the other way encountering the more brutal signs of a throwback, a decapitated head and a severed foot. During the paintings gestation period, the news was flooded with stories of a continuing war, of atrocities, natural disasters and corruption. Paintings have a mind of their own, once started they take the artist in a direction, and either subconsciously or by intent, life events become part of the process. This is in part what I was referring to above about how the time affects the imagery of the painting. Is that just a vase with flowers in the center of the painting, or is it some dreadful fireworks from a bomb which just killed a family? This kind of recursive interpretation, could go on for hours, the painting is an sheaf of images capable of constantly unfolding to engage the viewer.

One final observation. "Progress: Real and Imagined" is also complex in its stylistic resolution. Eisenman's painting, firmly structured, runs the stylistic gauntlet from the sweeping to the intimate. The little "throwaway" pictures in the studio are fully resolved in their own right. Her painterliness traverses a range from cursory to crusty congealed passages. It is obvious these variations are by choice, not constraint, for her observational powers are keen as seen in the rendering of the jeans of the artist at work. By expanding her range of execution, she in effect, detaches it from "style" and allows it to function as a tool of expression.

Nicole Eisenman's painting, Progress: Real and Imagined is an ambitious statement, an expansion of her vision. It is the type of painting I was hoping to see at the start of a new century, it is Future Modern.

Nicole Eisenman "Untitled" 2006

Oil on Canvas, 18 inches x 14 inches

All photos from the Leo Konig Gallery website, used without permission

PS:

I wanted to extend a special thanks to James Wagner and Barry Hoggard for introducing me to the artist.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)